Born on August 4, 1937, in Hiroshima. She was eight years old when she experienced the atomic bombing 2.4 kilometers from the hypocenter in Ushita-machi. A graduate of Hiroshima Jogakuin University, she married Kaoru Ogura in 1962. After his passing, she fulfilled his wish and founded Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace in 1984. She has since worked as an interpreter and coordinator. She gave her first testimony in English at the first World Conference of Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Sufferers held in New York in 1987. She now shares her experience with around 2,000 people a year. At the 2023 G7 Hiroshima Summit, she shared her hibakusha testimony with world leaders, including Ukrainian President Zelenskyy. In 2024, when Nihon Hidankyo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, she spoke at the memorial forum in Oslo, Norway.

I remember the streets being full of soldiers. My father ran a sweets wholesaler, so we had access to sweets even during the war. But as the war worsened, raw ingredients stopped arriving, and my father began operating a grindstone factory to meet military demand.

Until the first grade of elementary school, we lived within one kilometer of what wouldlater become ground zero. We then moved to a location 2.4 kilometers away. That’swhere I became a second grader—and where I experienced the bombing on August 6.

That day, the air-raid sirens rang in the middle of the night. It scared us. They kept sounding even into the morning, and we kept going in and out of the air-raid shelter. My father said, “I have a bad feeling—don’t go to school today.” His hunch was right.

At 8:15 a.m., I was standing on the road behind our house. I remember a flash of light, followed by everything turning white. I was thrown to the ground by the blast and lost consciousness. When I opened my eyes, everything was pitch black. I thought it was night. There wasn’t a sound. The first thing I heard was my little brother crying. Inside the house, shattered glass from the windows covered the walls, the ceiling was gone, and the roof tiles had blown off.

I stepped outside again, still confused about what had happened. That’s when black rain began to fall—rain laced with uranium and other radioactive materials. My clothes became dotted with stains.

Thankfully, my family—my parents and siblings—were not seriously injured. My father, who should have been near the hypocenter at the time, was delayed leaving the house because he had trouble putting on his gaiters. That delay saved his life. One of my brothers, who had been evacuated to the countryside, was also safe. Another brother was behind Hiroshima Station and said he saw the B-29 flying. He saw something small and black, like a speck of dust—what we now know was the atomic bomb. Right after he saw it fall, the B-29 made a sharp turn and flew away. He was watching that plane and didn’t see the actual explosion—if he had, he might have been blinded.

He made his way home, saying, “Hiroshima is a sea of fire.” Until then, we thought the bomb had fallen only in our neighborhood. That’s when we understood the scale of the devastation. Later, I learned that some of my classmates who had gone to school and were in the playground that morning were badly burned.

The bomb’s effects were different for everyone. Even if people were in the same area, whether they were burned, survived, or died depended on exactly where they were and what they were doing at the time.The fires from the hypocenter spread and burned all night. Hiroshima has seven rivers, and many people jumped in to escape the flames. Even animals like horses plunged into the water, and the rivers were packed with the dead and dying.

The next day, I climbed the stone steps of a nearby shrine and looked out at the city. Everything was gone. I could clearly see Miyajima Island in the distance. I remember thinking, “The city has disappeared.”

People fled to shrines and temples that had been designated as evacuation sites. My house was near one of those shrines, so the road in front was lined with people, walking in silent rows like ghosts. Their hair had burned, and the smell was overwhelming. It looked like they were carrying something in their hands, but it wasn’t objects—it was the skin hanging from their arms. They held their arms out in front of them because it was too painful otherwise. These lines continued for days. At the shrine, there were no medics— just one soldier applying what looked like oil to severe burns.

Many injured people came to our house, including an uncle with glass shards in his back.

Every day after the bombing, I saw people die right in front of me. Some didn’t even appear burned but still died from the effects of radiation. My father went to the park every day to help cremate the bodies. Flies swarmed over the wounded, and our job as children was to wave fans to keep the flies away.

The only word the injured could speak was “water.” One day, a man grabbed my ankle and pleaded, “Water…” I drew water from a nearby well and gave it to him. He drank it and died moments later right in front of me.

Back then, I didn’t know that giving water could worsen their condition. That memory became a trauma I couldn’t talk about—not even with my family—for ten years. At night, I would relive the moment over and over again.

Ten years later, I finally shared the experience—with a foreigner. I still remember the words they said to me:

“It’s not your fault.”

More than 2,500 children were orphaned by the atomic bomb. Many children who had survived due to evacuation returned to a scorched Hiroshima, only to find that their families were gone. They took shelter in the few buildings left standing and tried to survive—some worked shining shoes, others resorted to stealing out of desperation.Supplies were scarce, and soon a black market appeared in front of the train station. Aid began arriving from America, especially from Japanese Americans who sent food, school supplies, and warm winter coats. I still remember how happy I was to receive an overcoat —it was so warm and comforting.

People often ask me, “Did you hate America?” But I didn’t feel that way at all. I thought ordinary Americans were kind people.

Back then, I was always hungry. To express this to the occupying soldiers, I began to learn English. The first words I memorized were: “Hungry,” “Give me chocolate,” and “Hershey’s chocolate.” That was the start of my journey with English.

Later, a program was created to support A-bomb orphans both emotionally and financially, through what were called “spiritual parents.” Americans acted as these surrogate parents—sending cards with messages like, “Happy birthday, [Name]!” To a child who had lost their parents, hearing their own name called with love must have been deeply moving.

At first, we didn’t even know what an “atomic bomb” was. Of course, we had no understanding of nuclear weapons or radiation. We just knew a new kind of bomb had been dropped—and some said it was poison gas. Since the flash of light was followed instantly by collapsing buildings, we called it pikadon—”flash-boom.”

It wasn’t until about 10 years later, during the rise of the anti-nuclear movement, that people began to learn the truth: Hiroshima had been bombed with a uranium-type nuclear weapon, and Nagasaki, three days later, with a plutonium-type.

Survivors tried to forget. We lived in fear of radiation. Even those without visible injuries or burns could suddenly die without warning. We didn’t know when it might strike— would we develop cancer? Leukemia? If we became pregnant, would our babies be born with disabilities? I have two children, and I lived in anxiety until they were born. Even if they were born healthy, if they caught a cold and took longer than usual to recover, I couldn’t help but wonder, “Is it because of me?”

Every survivor felt this way. We hid the fact that we had been exposed—because even within Hiroshima, there was discrimination. We couldn’t tell anyone. All we could do was work hard and try to survive each day.

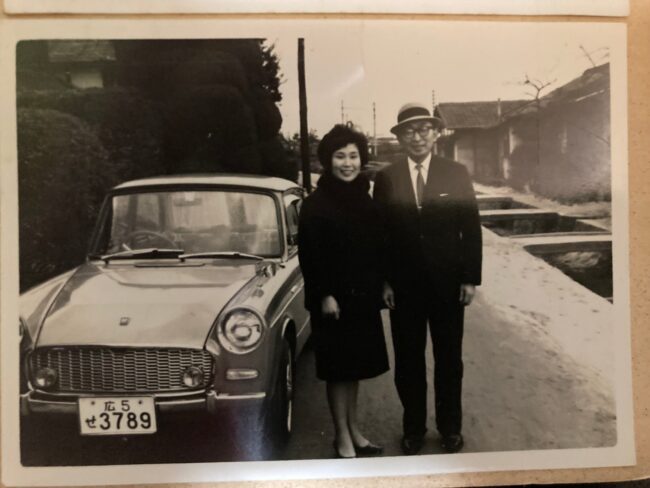

My husband was a bilingual Japanese American born in Seattle. During his lifetime, he served as Executive Director of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation and Director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. In 1979, while drafting the Hiroshima Peace Declaration for August 6, he passed away suddenly from a subarachnoid hemorrhage at the age of 58. I was 41.

Not long after, a foreign journalist who had been close to both of us contacted me and asked if I could interpret. Though I had majored in English literature at university, I had spent my married life as a homemaker, raising children and caring for my aging parents. But with the journalist’s encouragement, I accepted the job.

From age 42, for about 20 years, I worked as a coordinator and interpreter for interviews with A-bomb survivors, especially with international journalists and media visitors.

One day, while interpreting for American high school students, they asked, “Could the testimony be given entirely in English? That way we could use the time more efficiently and have a Q&A session, too.” That’s when I decided to give testimony in English myself. I wanted students from a nuclear-armed country like the U.S. to fully understand what happened during World War II, to grasp the terrifying reality of radiation, and to grow up into responsible adults.

Nearly 40 years ago, I spoke in the U.S. before a group of 140 people. Every single person believed: “Because the U.S. dropped the atomic bombs, World War II came to an end. The Japanese were saved.” That’s what they said they had learned in elementary school.

I responded, “Yes, the war did end. But why, just three days later, was another atomic bomb dropped—this time on Nagasaki, using a different kind of plutonium bomb instead of uranium? Was it a military necessity… or an experiment?” A debate broke out.

Thirty years later, I visited California. Elderly people who had lived through WWII came to hear me speak. This time, they wept and said, “We didn’t know.” One veteran said, “Keiko, we used to be enemies. But not anymore. Nuclear weapons must never be used again,” and hugged me. A woman in a wheelchair told me, “I’ll never be able to visit Hiroshima. But today I realized that not knowing is a kind of sin. My role now is to tell others. I will tell my daughter, and she will tell her children.”

In 2024, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations received the Nobel Peace Prize. For the first time, survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki were invited to share their testimonies at the commemorative forum in Oslo, Norway. While there, a child I had once met in Hiroshima came to see me and invited me to speak at their middle school. I spoke to 200 students. They all cried and said, “We’ll never forget this day.”

Whenever I left the hotel, local Oslo citizens waited for me outside in freezing temperatures, asking for autographs. They had seen my testimony during the G7 Hiroshima Summit, which had been covered by some 6,000 members of the international press. I was amazed at the power of the media—and grateful that I could speak English.

What I want most to tell people is: love others.

Love your family, your friends—love them so much that you can’t imagine life without them. War steals those lives. Nuclear weapons not only kill today, but rob us of our future. Don’t turn away. Know.

When you see the personal belongings of a bomb victim, imagine: What were they thinking as they wore those clothes? What did their family feel? Please, use your imagination and sensitivity.

If more and more people think this way—across borders and nations—we can truly create a better world.

-650x521.jpg)

____________________

この記事はライトハウスハワイ2025年8月号掲載時点での情報です。